CoHo’s Blog makes a comeback!

Welcome to the author of this essay, Kimberly Fanshier, who joins CoHo as a marketing intern this term while earning her master’s degree in Literature from PSU.

In 1892, the year she first published “The Yellow Wallpaper,” Charlotte Perkins Gilman was a writer and a mother from New England, living in California. She had, several years past, been a patient of the famous, eccentric physician S. Weir Mitchell – evangelist of the notorious “rest cure” treatments that Gilman gruesomely examines in her now-canonical tale. Although the synaesthetic, suffocating patterns of Gilman’s absorbing, taunting wallpaper and the furtively scribbling narrator who details it are now mainstays of collections, anthologies and undergraduate coursework, early readers and critics did not accept Gilman’s provocative critiques generously. Upon receiving “The Yellow Wallpaper” as a submission, Horace Scudder, the editor of the prestigious, cultural taste-maker the Atlantic Monthly, promptly rejected her ghostly, harrowing tale with amused shock, stating “I could not forgive myself if I made others as miserable as I have made myself!” (Shumaker 588) Her story eventually found its initial home in the respectable, but not nearly as lauded New England Magazine. It was accompanied by a series of illustrations of a woman falling into aggrieved hysterics, the placement of which was presumably outside the control of the author.

Other critics uneasily received the story as a reproduction of gothic ghost stories popular earlier in the century that featured eerie atmospheres and unexplained phenomena, and let the piece largely alone. William Dean Howells, an early supporter of Gilman and other women writers of the period, reprinted her story thirty years later in his collection Great American Modern Stories. But even he somewhat apprehensively introduced it as “terrible and too wholly dire” to appear comfortably in printed anthologies alighting in drawing rooms and respectable parlors. Later critics questioned this response, arguing that the reading public, so recently exposed to the popularized tales of horror by Poe and other late romantics, were not too fragile to register just any tale of insanity and delusion. As Susan Lanser writes, editors like Howells and Scudder, and presumably their reading publics, were “were surely balking at something more particular: the ‘graphic’ representation of ‘raving lunacy’ in a middle-class mother and wife that revealed the rage of the woman on a pedestal”(Lanser 417-18).

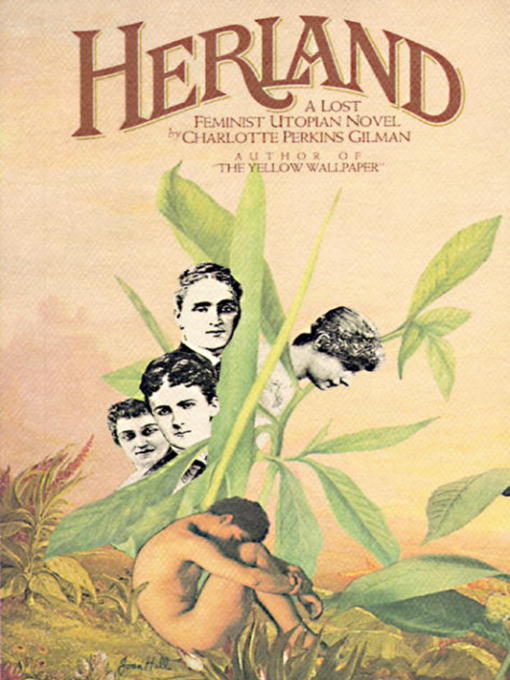

Although Gilman remained an active writer, speaker, and activist until her death in 1935, “The Yellow Wallpaper” faded from the public view and critical conversations. (A great deal of popular fiction penned by women in the 19th and early 20th centuries suffered the same fate during the period, which was marked by the development of literary criticism as a specialized field, a new spirit of hyper-canonicity, and the dominance of certain powerful figures with specific tastes and distastes). And after her death, most of her works – including the Herland triology, a utopian fantasy of a hidden, all-female culture marked by peacefulness, generosity, and a deeply disturbing commitment to racial purity and eugenics, her economic theories of gender inequality and her feminist manifestoe – were largely lost, hidden, and forgotten for fifty years.

The development of feminist literary criticism in the late 60s and early 70s, however, placed an emphasis on rediscovery of literary pasts and cultural histories. Feminist critics scoured libraries and catalogs, and worked to reconstruct the bodies of work of dozens of forgotten, ignored, disparaged or disregarded novelists and writers, like Edith Wharton, Susan Glaspell, Kate Chopin, Sarah Orne Jewett, and Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Elaine Hedges came upon the story in 1972, and described it as a “small literary masterpiece,” (Shumaker 588) “The Yellow Wallpaper” soon inspired a rush of attention from other interested scholars, like Annette Kolodny and Sandra Gilbert, who found an impossibly powerful symbolic parallel in the story of a woman writer confined and reduced to a fracture of the self, and the actual fate of the story in modern America. Gilman became a hero of the new feminist movement, and “The Yellow Wallpaper” a rallying testament and flagship piece of literature. It was proof of how literary criticism had failed and hurt women writers, and it was an incredible story of madness, triumph, and despair.

However, although the 1970s brought a wealth of lost literature, art and new frontiers of theory and criticism, it is essential to realize that these early efforts almost entirely focused solely on the neglected works and lives of upper middle class white women, based largely in New England. Indeed, such an observation actually stands in as a criticism of early second-wave feminism as a whole. In many ways, this movement was one that was supremely interested in the needs and realities of only a very specific kind of woman: one that was rich enough, straight enough, U.S. born enough, and, most importantly, white enough.

And Gilman, although a brilliant, profound thinker and writer, likewise developed violent, racist ideas in her non-fiction and fiction alike. In 1989, Susan Lanser penned a critique called “Feminist Criticism, “The Yellow Wallpaper,” and the Politics of Color in America” which set off a new era of reading for the complicated story. After carefully detailing the story’s history, it’s erasure, and its new pre-eminence, Lanser argues that, due to its status as a somewhat sacred text of 1970s feminism, and perhaps because of the faults of that particular movement, readers have condemned Gilman, her narrator, and the lurking, creeping women of the wallpaper to the original illegibility, confinement, and erasure that they originally railed against. Rather, everyone is reading for what they want to see, instead of what is actually there – and they are thus missing a huge piece of Gilman’s narrative.

Lanser returns to the history of the late 19th century American obsession with anti-immigration platforms and sharply developed racism against people perceived to have Japanese or Chinese ancestry in particular. Reading the text “within the discourse of racial anxiety”(Lanser 427) necessary to actually read and write about writing from the 1890s, Lanser develops an intricate, compelling argument that does not necessarily condemn the text as racist, xenophobic, and unforgiveable – but complicates it with the history of the turn of the century’s racist rhetoric regarding “The Yellow Peril,” the perceived failure of white women to reproduce properly, and the white terror at the thought of immigrant women, poor women and women of color reproducing at higher rates. The crimes of Gilman’s narrator, then, can be read as not only refusing to comply with coded gender behaviors, but actively endangering the dominance of her race by going crazy instead of having more babies.

When we consider the history of hysteria and the particular kind of misogyny and sexism that the story describes, we also can see that even oppression is deeply coded by class and race. In her article “The Race of Hysteria,” Laura Briggs explores how the invention of the “disease”, and the “nervous conditions” that so many white women were diagnosed with were predicated on the ideologies of “over-civilization” and “savagery” that were used to class black women, immigrant women, and even poor women as others, and how black women were not only perceived as being impugn to the symptoms, but that these fabricated “differences” of body were weaponized to further invent caustic, violent narratives of race and racism that address and oppress women of color.

If we are to read thoughtfully, it is impossible to read any American narrative without comprehending that the existence of race, while perhaps not fore-fronted by the author, is a defining, shaping feature of the text. The experiences of “The Yellow Wallpaper’s” narrator are precisely those of an upper middle class white woman of the period. It does not discount her suffering, struggle, or experience to recognize this fact, but to do the opposite – to assume, silently and willfully blindly – that these experiences are representative of the whole of womankind – or even American womankind of that precise period – decisively enacts violence on the histories, memories, stories, and legacies of women of color living in the United States in the 1890s, and today.

“The Yellow Wallpaper” is still widely read, and criticism on the work continues to grow and complicate. Present scholars of post-colonial studies, queer theory and psychology have continued to open the story and apply pressure to its dangerous, uneasy portions. And the exploration by dramatic artists, moving the story into three dimensions and real time, can push our bounds of interpretation even further – allowing us more and more opportunities to peel the paper off of the walls.

By Kimberly Fanshier

Citations:

Briggs, Laura. “The Race of Hysteria: “Overcivilization” and the “Savage” in Late Nineteenth-Century Obstetrics and Gynecology.” American Quarterly 52.2 (2000): 246-73.

Lanser, Susan S. “Feminist Criticism, “The Yellow Wallpaper,” and the Politics of Color in America.” Feminist Studies 15.3 (1989): 415.

Shumaker, Conrad. “”Too Terribly Good to Be Printed”: Charlotte Gilman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper”” American Literature 57.4 (1985): 588.