by Kimberly Fanshier

Sue Mach’s The Yellow Wallpaper begins by fore-fronting one of the hottest philosophical debates of late 19th century England and America. Perhaps the rip-roaring rhetorical conflicts of world-class frenemies John Stuart Mill and Herbert Spencer don’t sound super thrilling or totally accessible. The questions that these guys were getting at, however – and the way that original author Charlotte Perkins Gilman and adaptor Sue Mach have woven them into an expressive narrative – help us continue to wonder about liberty, social constructions, and perceptions of reality right now.

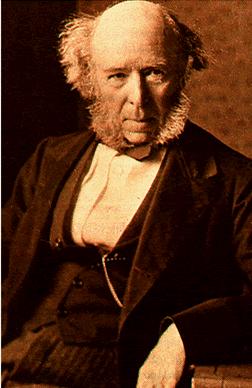

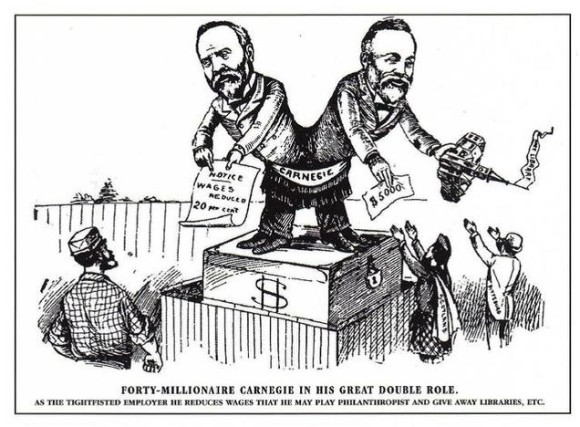

We remember Herbert Spencer as the man who coined the term “survival of the fittest” – a soundbite currently associated with draconian economic policies and feeding the rich as much as it is with the specialization of Galapagos finch beaks. And while he might not be quite the father of Social Darwinism that popular history remembers him as, his ideas about society flourishing via unfettered competition and a lack of government meddling in business and property are not unfamiliar to political stumping you’ll hear on the 2016 campaign circuit. A philosopher who ascended to rock-star status in the wild Victorian world of sociology and lecture circuits, Spencer championed science over religion and mysticism, wrote the first textbooks for the burgeoning field of sociology, and staunchly opposed government aided social reforms. His legacy is now pretty bound up in the histories of our fabled capitalists of the gilded age – Andrew Carnegie and other massively powerful titans of industry cheerfully grabbed hold of Spencer’s philosophies to justify their shocking fortunes and a new era of injustice in American society.

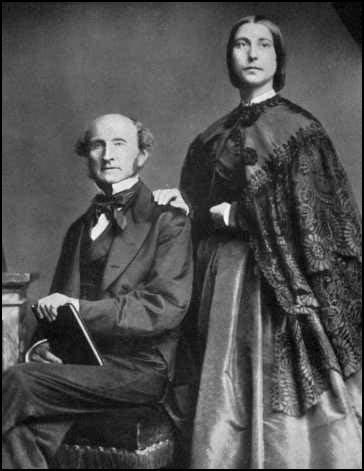

Although Herbert Spencer was one of the first – and perhaps last – philosophers to be a bestseller and household name, history hasn’t been quite as kind to his theories. His popularity set him up for criticism later, and the 20th century did not take his writings very seriously. His friend, colleague, and theoretical opponent John Stuart Mill, however, is still regularly assigned on high school and undergraduate reading lists. Mill’s famous essay “On Liberty” also questions the will of the individual and the ability of a person to express freedom and self in a society that wields some type of control over people and their actions. However, Mill insisted (with a lot of help from his wife, Harriet) that the “tyranny of the majority” was as bad, if not much worse, than the tyranny of an authoritative state. By noting and emphasizing that people in power have a wider reach and the ability to inflict control over disempowered people, Mill critically altered the kind of discourse that Spencer was engaging in.

Although people today don’t so openly and expressly declare that natural law makes some people just better than other ones, it’s unnerving when stuff that sounds a lot like social Darwinism still seems pretty widespread in public discussions about diversity, inclusion, social justice, and economics. So why exactly is defaulting toward “nature,” in the spirit of Spencer, so potentially dangerous?

When someone invokes the idea of “natural law” as a justification for their cutthroat economic policies or as an explanation of why some people have more power and rights than others, it’s important to notice – where are they standing when they are speaking?

It’s simple for a character like The Yellow Wallpaper’s John – a property owning, capital wielding physician whose voice is considered authoritative and dependable – to explain that he is socially dominant simply because it’s the “natural” way things are. For Charlotte, however – a person with few legal rights whose voice is not even considered – such leaps are not so appealing, or possible.

It’s easy to think of “nature” as descriptive, instead of prescriptive – but it’s not right. It’s easy to say, “Men invent things, become doctors, get published and win Oscars for directing because they are, apparently and obviously, better at these things! Look at all of these things that they have made!” It’s harder to say, “The world is built for certain men to succeed in, and other people do not even have the chance.” Such statements are frightening and disturbing. They not only shake up the world as we know it and wish to see it, but they demand immediate and extensive reaction.

Ideas about what is “natural” are often not informed by honest and thorough observation of intricate realities and long-reaching histories. They are constructed after the fact, to cement and justify certain social conditions as they stand, and to quiet down trouble makers. Remember Simone De Beauvoir’s famous statement, that one is not “born” a woman or a girl – but rather, is “made” one. Language, culture, and philosophy can retroactively invent what people are like, what they’re supposed to be doing, and whether we should listen to them or not. And we should be vigilant about such inclinations.

While Herbert Spencer purported to believe in liberty above all else, the way that he helped construct backwards notions of the “natural” roles for people hurt our chances at liberty more than anything. The Yellow Wallpaper makes a space for us to question those presumptions. It asks us how someone can find a way to break free from the subconscious internalizations of an oppressive “natural order” – and what they might look like on the other side.